The mindfulness movement has grown in popularity over the past two decades, but research on its effectiveness is still catching up. According to a West Virginia University neuroscientist, increasing the precision of mindfulness research can multiply the potential benefits that meditation and similar practices impart.

The mindfulness movement has grown in popularity over the past two decades, but research on its effectiveness is still catching up. According to a West Virginia University neuroscientist, increasing the precision of mindfulness research can multiply the potential benefits that meditation and similar practices impart.

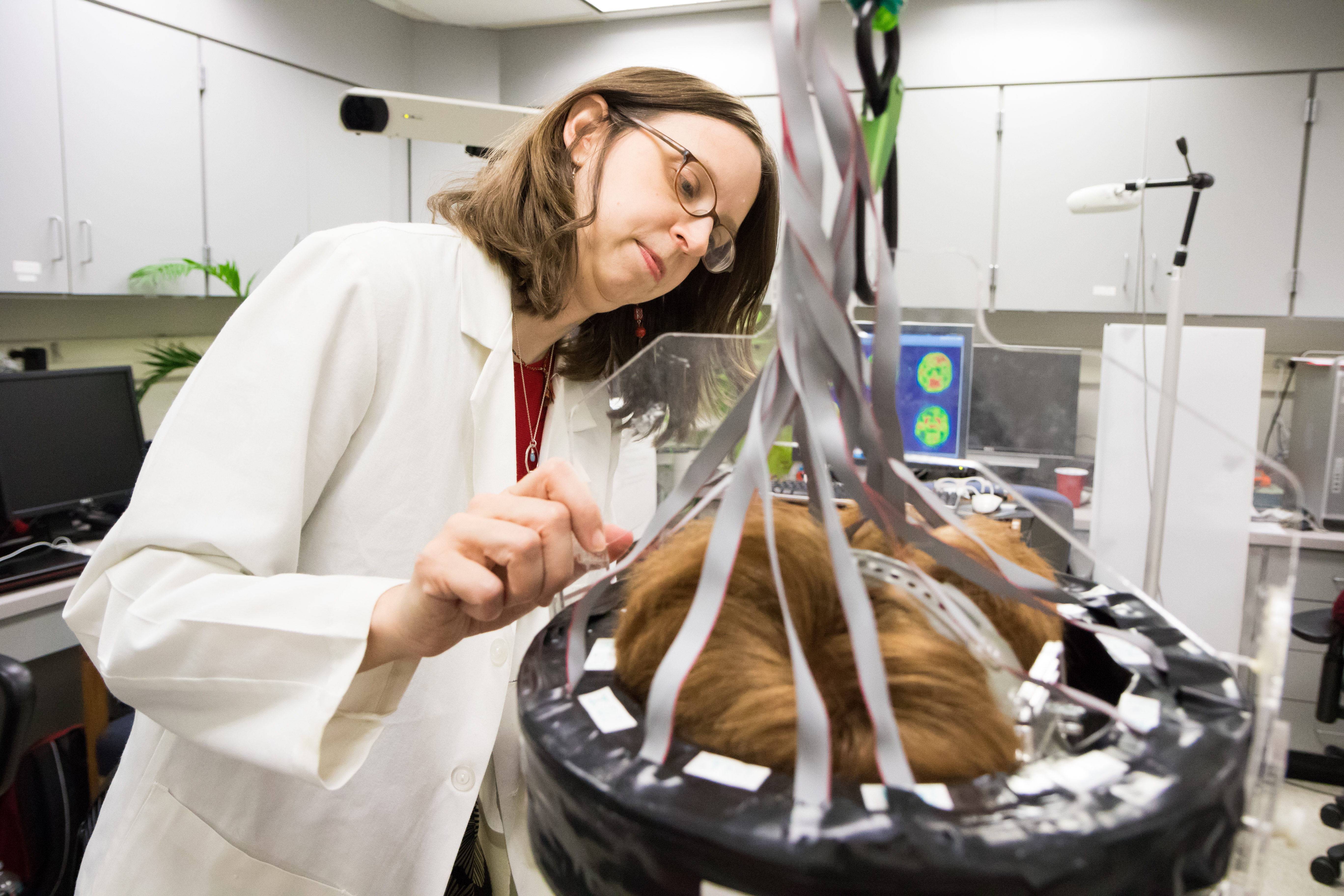

A paper coauthored by Julie Brefczynski-Lewis, assistant professor in the WVU Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute, explores the need for greater rigor in mindfulness research. It also recommends ways to obtain more precise data from mindfulness studies and to communicate findings more accurately. The paper was recently published in Perspectives on Psychological Science.

In the paper, the authors describe mindfulness as practices, processes and characteristics related to attention, awareness, memory and retention, and acceptance and discernment. These practices have become important in areas such as psychology, psychiatry, medicine, neuroscience and beyond.

Brefczynski-Lewis says that based on meta-analysis, which measures the robustness of the results of multiple studies combined, mindfulness programs can be moderately effective for anxiety, depression and pain, similar to the effectiveness of common antidepressants like Prozac.

“Unlike drug studies, the people signing up for mindfulness are more likely to self-select. In other words, they want to try mindfulness,” said Brefczynski-Lewis. “We still don’t know if it will have a significant benefit in those who aren’t as open to it and for other conditions.”

Researchers are also still exploring the most effective “dosage” of mindfulness practices and what Brefczynski-Lewis calls the mindfulness “magic ingredient.”

To help illuminate these aspects, the paper includes recommendations that researchers carefully define what mindfulness and its related terms entail, venture beyond questionnaires to gather data, use randomized control trials, account for any negative side effects that mindfulness practices cause, and communicate findings accurately and without hyperbole.

Brefczynski-Lewis said one of the goals of the paper was to prompt researchers to think about these areas, and find ways to overcome the related challenges.

For example, could researchers recruit larger numbers of subjects for their studies, and similarly, could such skeptics be included on the research team to reduce bias? Could researchers augment self-reported survey data with measurements of subjects’ cortisol levels, their heart rates or the time they take to recognize positive or negative words that flash on a screen?

The paper’s authors have diverse specialties, from psychology to philosophy to mindfulness instruction. Brefczynski-Lewis, who has been involved in mindfulness research for more than a decade, brought a neuroscientist’s perspective to the issues.

“Aside from basic neuroimaging expertise, I hoped to provide a historical perspective to this manuscript,” she said.

She explains that in the early days of mindfulness research, experts were concerned about inaccurate reports of effectiveness. Researchers did not want small-effect-size studies – such as a study of how 20 people are dealing with pain – to be misinterpreted as proof that mindfulness could cure pain with no side effects.

In fact, she says that in some cases, individuals could do themselves more harm than good if they undertook a mindfulness practice without a healthcare provider’s guidance. And some might abandon mindfulness practices prematurely if their practice isn’t an immediately transcendent experience or if they have unsettling experiences but lack anyone to check in with.

“What I’m hoping will come out of this is a more nuanced way in which mindfulness is presented,” said Brefczynski-Lewis. “What we really want is for the research to benefit the public and reduce harm.”