Biology students at West Virginia University are studying the impact of climate change on the forests of the Appalachian Mountains.

Biology students at West Virginia University are studying the impact of climate change on the forests of the Appalachian Mountains.

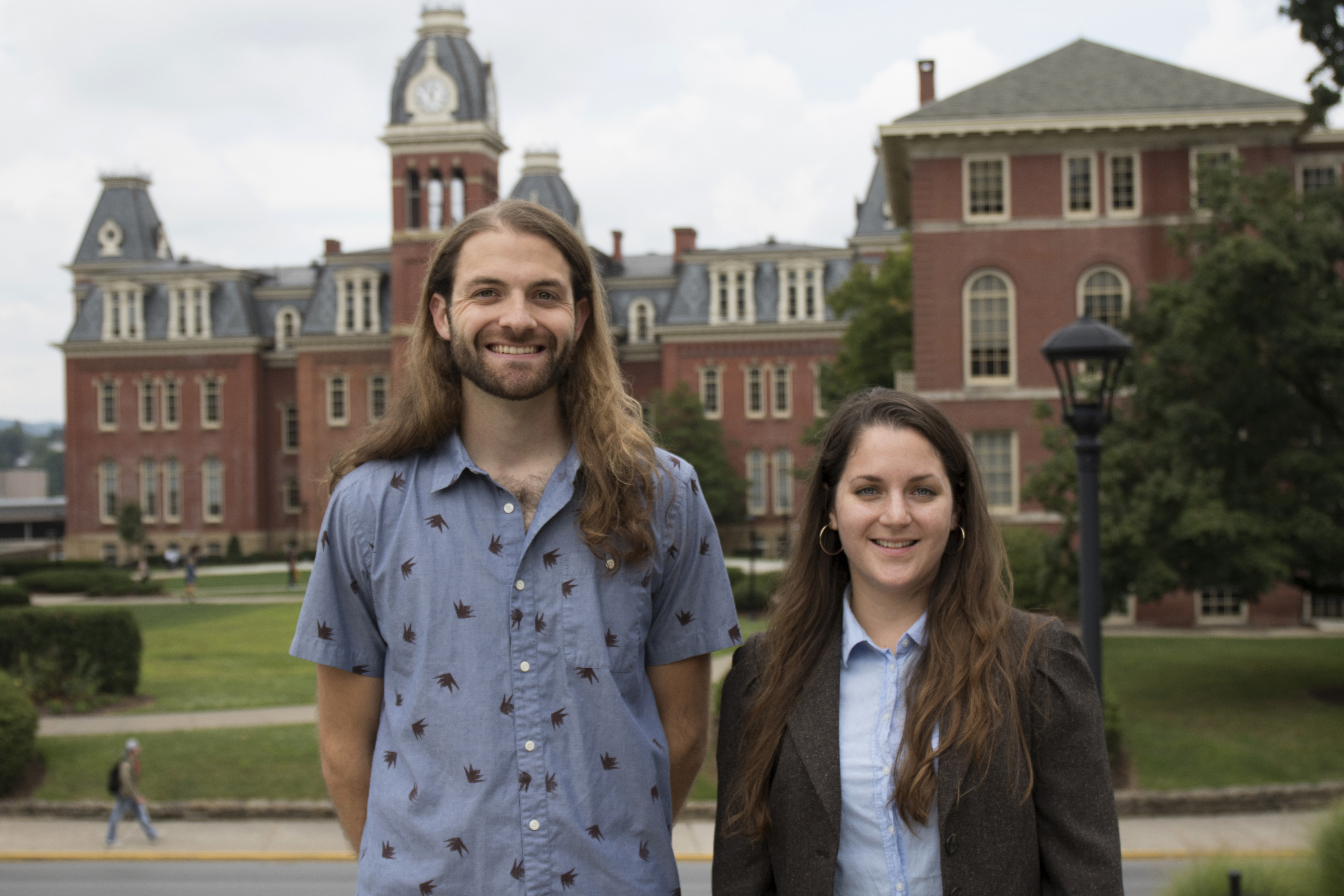

Justin Mathias and Nanette Raczka, Ph.D. students in the Department of Biology, have received Smithsonian Center for Tropical Forest Science-ForestGEO grants to support their research.

“These grants are prestigious and very competitive to get,” said Richard Thomas, chair of the Department of Biology. “It is very unusual that one university gets more than one in a year.”

Mathias is using his $13,000 grant to investigate changes in tree growth in the Appalachian Mountains over time and identify the drivers of those physiological changes. He will use a site in Front Royal, Virginia, that is part of the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute’s ForestGEO network.

“Trees can’t get up and move if they become stressed by their environment. They just deal with it in some way,” Mathias said. “They are telling us a story; we just have to figure out what that story is.”

By studying stable isotopes and tree rings, Mathias will identify the elements that comprise the trees, such as carbon, nitrogen, oxygen or sulfur, to better understand their physiology.

“Each of those different elements tell you something different about how the tree is functioning. When a tree adds on wood, the carbon that it gets to form biomass comes from carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Given that, at least in the forests around the Appalachian Mountains, you have a growth ring every single year added on,” Mathias said. “It’s a really neat way to retrospectively examine both the physiology and the environment the tree is in, in a given time period.”

Through her $7,000 grant, Raczka will incubate soil from the same ForestGEO network plot to study the complexities of leaf litter. Using a technique called Quantitative Stable Isotope Probing, she will examine how soil microbes process carbon from leaf litter.

“This is a new technique, but it’s really useful because we can measure the amount of leaf litter that’s incorporated into the microbial biomass. We can see what microbes, whether they are fungi or bacteria in the soil, incorporate what type of leaf litter,” Rackza said. “This is really cool because it’s a critical step in understanding how carbon is stored in the soil and how it’s utilized from the inputs of the tree and the leaf litter to what stays in the soil or what is respired.”

Raczka learned qSIP from her research experience in Ember Morrissey’s lab, an assistant professor of environmental microbiology in WVU’s Davis College of Agriculture, Natural Resources and Design. She is applying the technique to her research with Assistant Professor of Forest Ecology and Ecosystems Modeling Eddie Brzostek, which focuses on below-ground interactions and potential responses to global change.

“It’s a great partnership with her because I can learn this molecular technique that’s new to us to incorporate something that we do in our lab,” Raczka said. “The interaction with the graduate students and the professors here has been the best part of my WVU experience so far. To be able to learn new techniques in different labs is a really great opportunity, and I love the cross-disciplinary collaboration.”