A team of researchers, including, Bruce M. Rothschild, M.D., a professor of medicine in WVU’s School of Medicine, recently uncovered a unique diagnosis for a dinosaur 78 million years after its death.

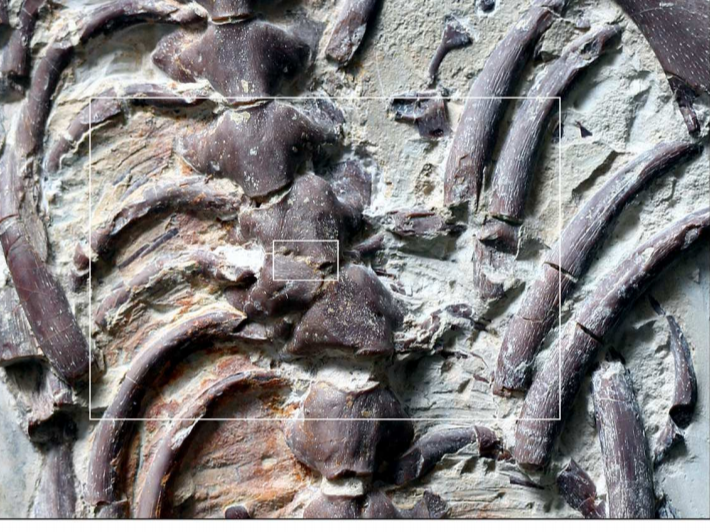

Looking at unique fossils collected in 1988, the team discovered that the fusion of the vertebrae wasn’t the sacrum as previously assumed. It was fused because it was a pathology of the specimen, and the bones were not sacral vertebrae; they were dorsal vertebrae.

While it’s not uncommon to find fused duck-billed-dinosaur vertebrae, these vertebrae are typically in the dinosaur’s tail, not in the middle of its spine. The condition likely impaired the dinosaur’s movement — a disadvantage if it was fleeing a predator, such as a tyrannosaur. The ailment may have also made it difficult for the duck-billed creature to move around in everyday life and defend itself.

The condition also affects mammals, including humans, and there is no cure. However, Its symptoms in humans are often treated with the anti-inflammatory drug sulfasalazine.

The condition also affects mammals, including humans, and there is no cure. However, Its symptoms in humans are often treated with the anti-inflammatory drug sulfasalazine.

The research, presented on August 23 at the 2017 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting in Calgary, Alberta, is considered one of the very few cases of fossil hemivertebra, a congenital developmental malformation caused by unequal development of the left and right half of a vertebral centrum or complete absence of either of them, resulting in asymmetry of the vertebra in a complete, articulated skeleton, which illustrates the effect of malformation on the whole body of the animal.

The results of the study were also published in an American open-access scientific journal PLOS One on September 21, 2017.

Read the article in Live Science.

Header photo credit: Courtesy Royal Tyrrell Museum